Yes, you heard me correctly. Do we need roads? Those long winding black things that snake their way through our built up areas and rural pastures. They’re almost everywhere and you’ve been on one in the last few days. I’m willing to bet you’re about 30 feet away from one right now. Well I want to question their necessity. I’m going to ask what a road fundamentally is and more importantly, what it means for the way we live in our cities.

Roads are one of those elements of life that go unquestioned. This should be surprising given that we have spread our lives out to live around them. As drivers or cyclists, we consider them as a network, planning how to connect them to find our destination. As pedestrians, we wait obediently at the edge for traffic to pass. Instead of being the elephant in the street they are considered so basic as to not warrant discussion. We debate how fast people should travel on them and where they ought to be but rarely whether they should be at all.

They haven’t always been here. We live in a historical anomaly where we travel longer distances more frequently than ever before. It’s not unusual to make a commute of a hundred miles or more on a daily basis. A hundred years ago this sort of journey would have required several days in a bumpy carriage. Several hundred years ago it would have been an unthinkable dream for someone who wasn’t a merchant or soldier to explore an unknown realm so far away.

The way we build roads is critically important because they constitute such a large part, literally and conceptually, of our cities. As well as the function of transport they are our largest shared space and the most frequent site of protest and conflict as well as togetherness. The choices we make about how to implement roads affect the vitality and colour of our lives not just because effective transport allows us to travel easily but because the format of our shared space as a society is determined to a large degree by how we choose to do so. It has an impact on the amount and quality of space each one of us has to live our lives.

Roads are the things between places. They are what we tend to fill in the gaps with between the things we build. Because they are exclusively designated for vehicles, the way we think of them creates a duality of things that are where we live our lives, generally buildings and occasionally parks and public squares, and things that are not where life cannot be fulfilled. Travel is a single aspect of life and not one people are likely to suggest is the most important or pleasant. In spite of this, we have dedicated an enormous amount of our cities to facilitating it. In the city of Los Angeles where roads run riot, 60% of it is assigned to roads.

This idea has largely emerged through the 20th century and is the consequence of a number of social, political and technological factors. We view roads as dedicated channels of movement that should never be impeded and the rise of the car has been a huge driver in creating this impression. As well as being the exclusive domain of vehicles, they are restrictive because you cannot drive through a row of terraced houses.

I might disappoint the most radical of you by admitting here that I’m not going to suggest that all roads should be immediately abolished. My purpose is to be more questioning than that. I want to dig through the layers of assumptions about what roads are and how they should be. Once we start toying with alternatives to roads, we are forced to analyse the composition of our cities as well. If we find all to be well and good then we can put the layers back with the knowledge that we now have a living truth rather than dogma. However I fully intend to reach in and shake the foundations of these assumptions so that you can no longer look at two brick walls and a layer of asphalt and say, ‘yes, that all seems acceptable to me.’

This essay is going to be fairly Anglo-centric, so lets take a moment to explore how different cultures have different understandings of this duality. Japanese addresses perhaps reflect these two parts more accurately. In Japan the blocks of buildings contained by streets have names, but the streets themselves are nameless. After all, it is really the life that emerges from the buildings that give character to the road rather than vice versa.

In Costa Rica the streets do not have numbers and all directions are given by proximity to a nearby landmark. This makes our means of navigation impossible, since the roads are almost irrelevant in this case. The models we hold in our mind are important, as we use them to inform our interactions with the world. A change as simple as considering the street the void rather than what surrounds it will affect one’s attitude in the microactions that construct the world - how you choose to react to the pedestrian that steps in front you for instance. Or your feeling towards a street party being held in your neighborhood.

In our effort to bust out of this conceptual straitjacket, perhaps we can take inspiration from science fiction for some alternative means of understanding what the voids between places are and how else we can compose the city.

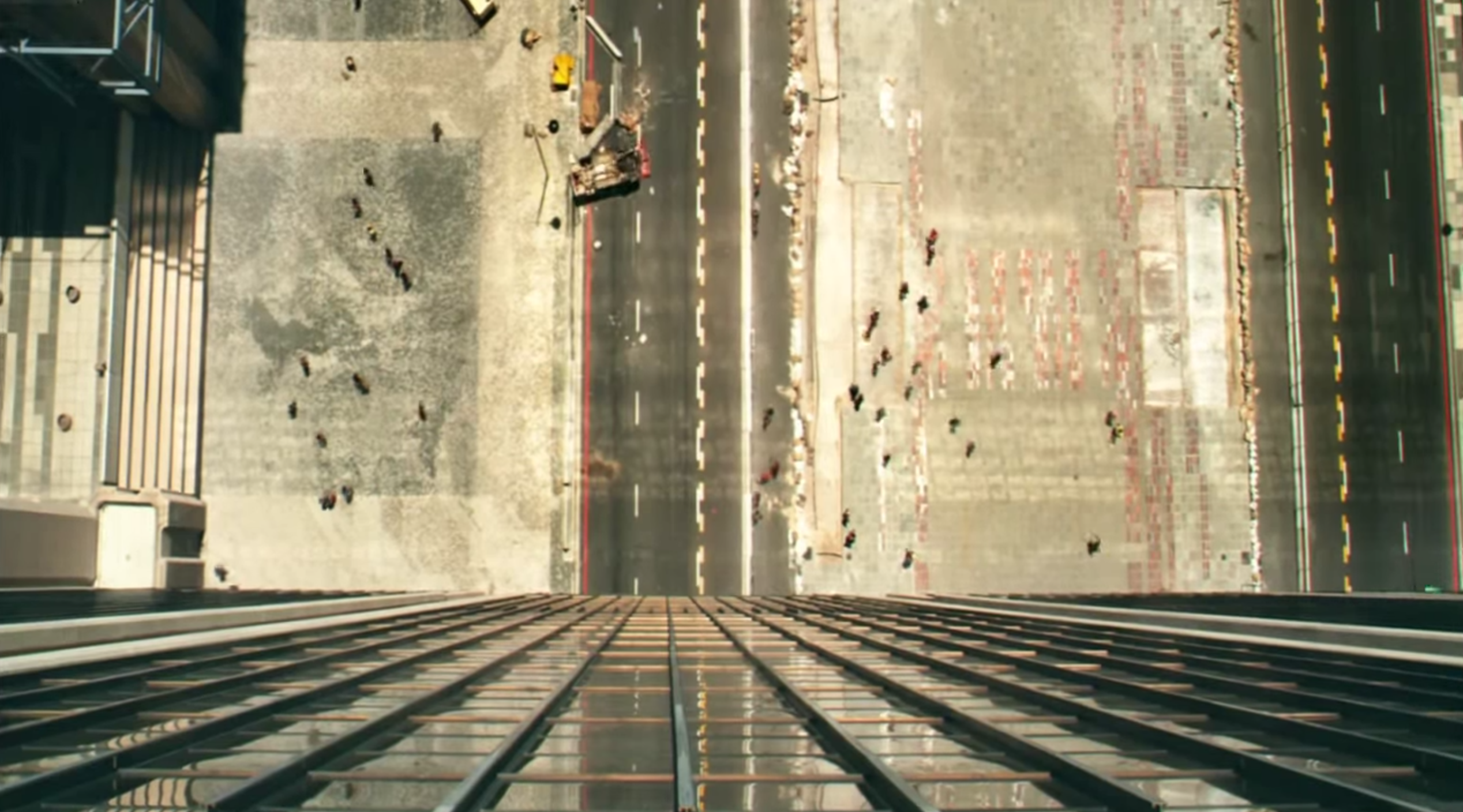

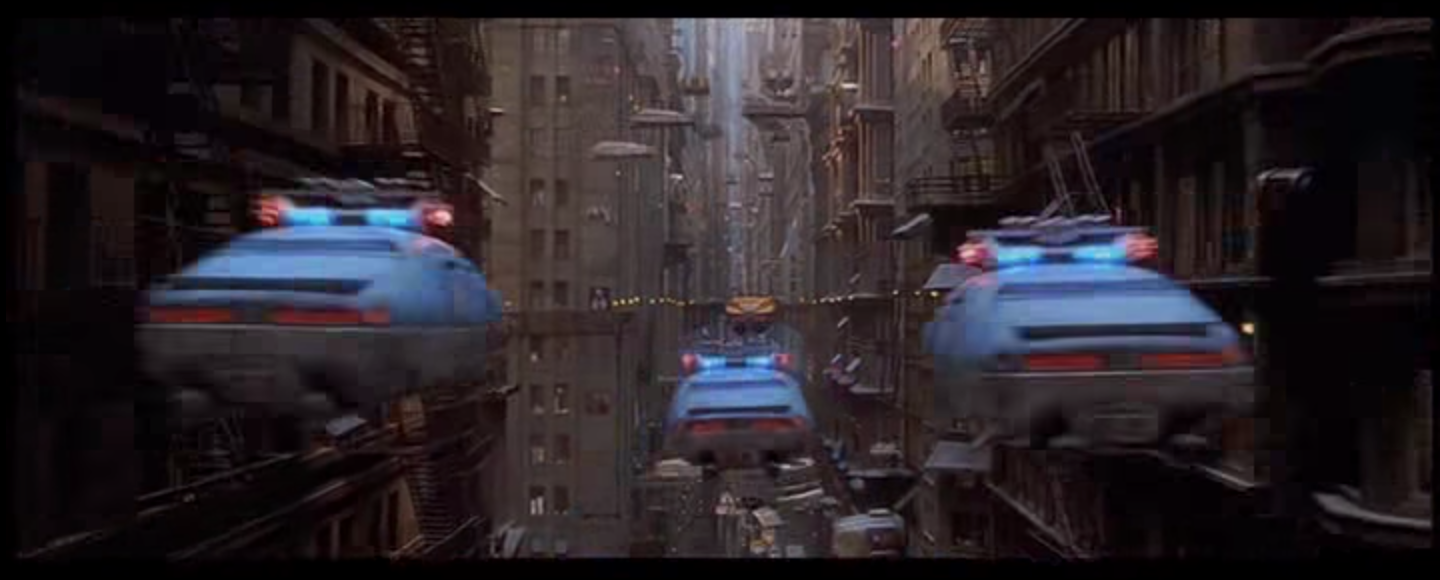

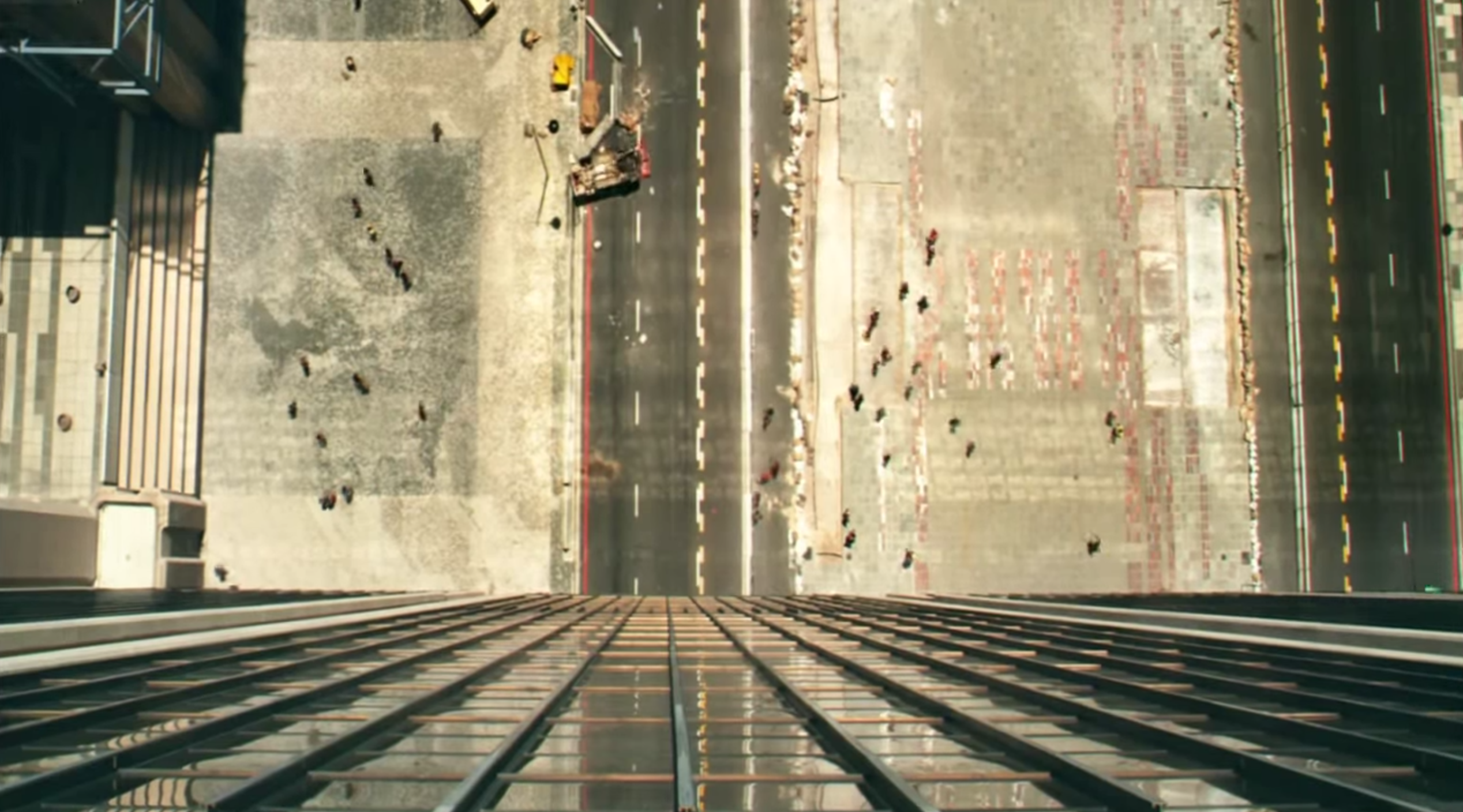

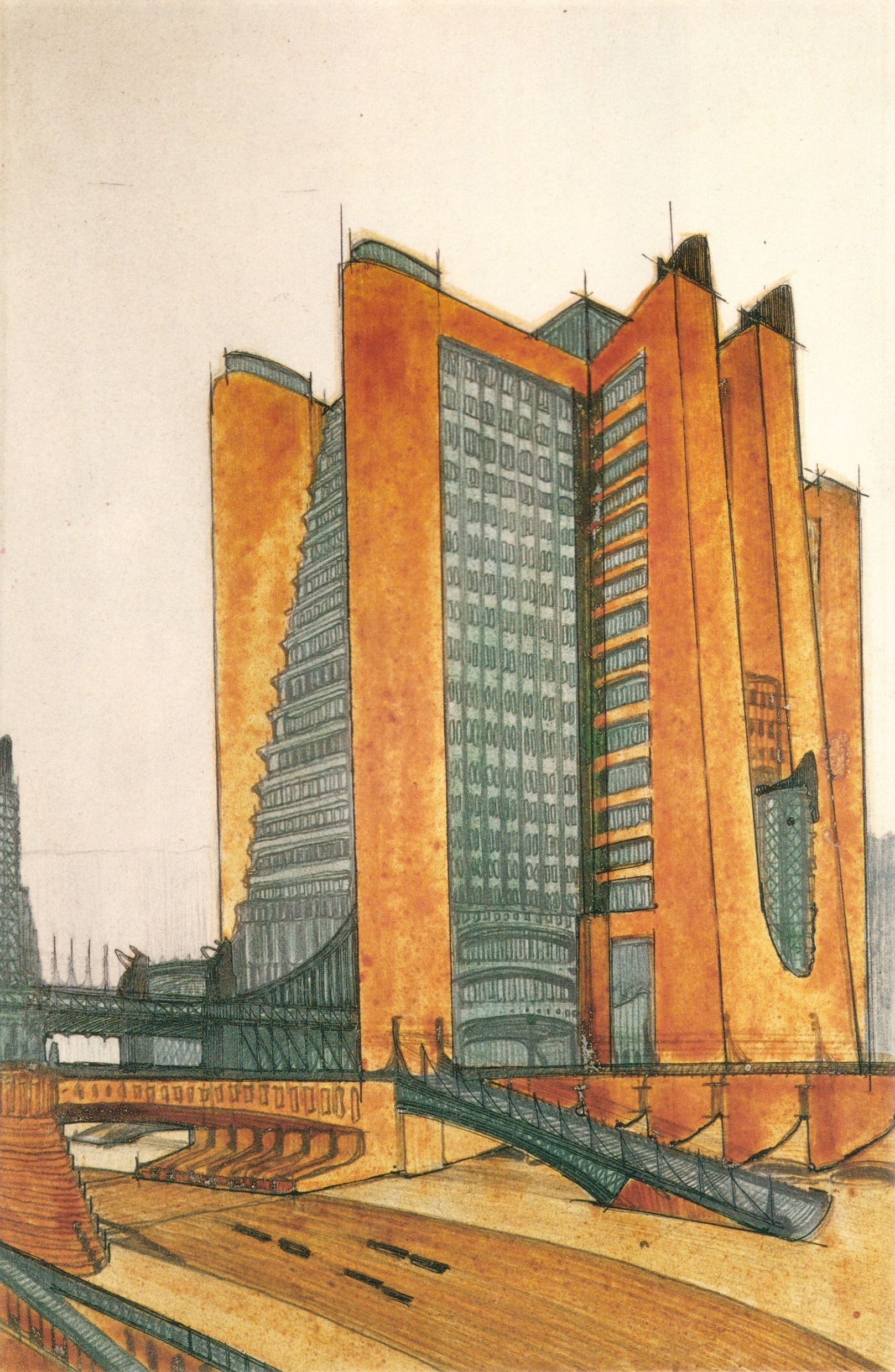

These are a couple of stills from the stunning dystopic scenes of the 1927 film Metropolis made by Fritz Lang. However, like most 20th century imaginations of the future, especially the earlier years, it is fairly unquestioning in its approach to roads. Most of what is proposed for the future is even more roads, wider and faster than ever before. At this stage, the car was a luxury for the rich only and we’re only just on the cusp where it starts to be seen as an agent of personal freedom. Hence vast roads are seen from the perspective of the driver zooming excitedly from one place to another rather than the community they sever.

Some credit has to be given for the innovation of a 3D city. Its citizens are not condemned to live their life on a single layer - trains and walkways rise through the sky passing from building to building.

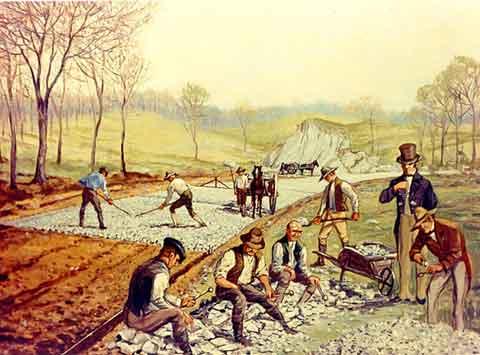

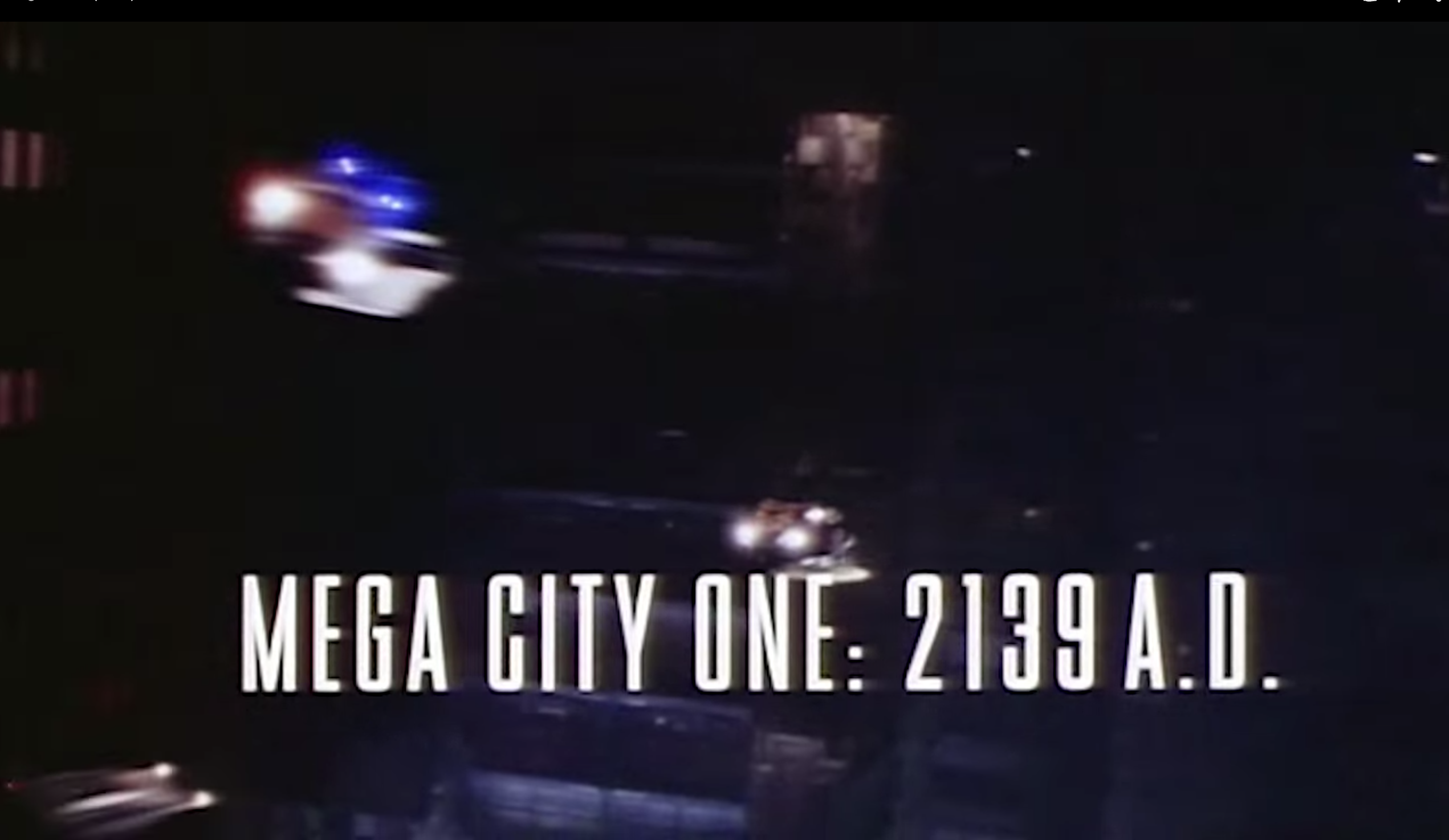

Flying cars have been a mainstay of science fiction for roughly the last 50 years. We see them in Blade Runner (1982), The Fifth Element (1997), Judge Dredd (1995), Minority Report (2002) and Dredd (2013).

Unfortunately while all of these films feature exciting new technologies that allow for speed and high speed mid air chases, they fail to question how the background structure of the city might change in response as a result. At most what we get is more layers of roads on top of each other. Minority Report is probably the most interesting in terms of roads because it features fully automated vehicles that come right up to the window of your tower block residence.

It should be noted as well that these are all dystopias, so we can choose to interpret the representation of transport as a reflection of our own worst qualities as a society. Interestingly, Demolition Man (1993), an apparently utopian vision of the year 2032 features this scene of driving with a background of skyscrapers set amongst vast green spaces and traffic free highways.

This vision comes straight from the 20th century architect Le Corbusier, someone we’ll return to later on. In his plan for a contemporary city of three million he was attempting to construct “a theoretically watertight formula to arrive at the fundamental principles of modern town planning”. There’s a phrase that ought to chill you. The cityscape above has not arisen over time from the actions of its residents based on their needs, but imposed on them through the application of a series of scientifically extracted principles.

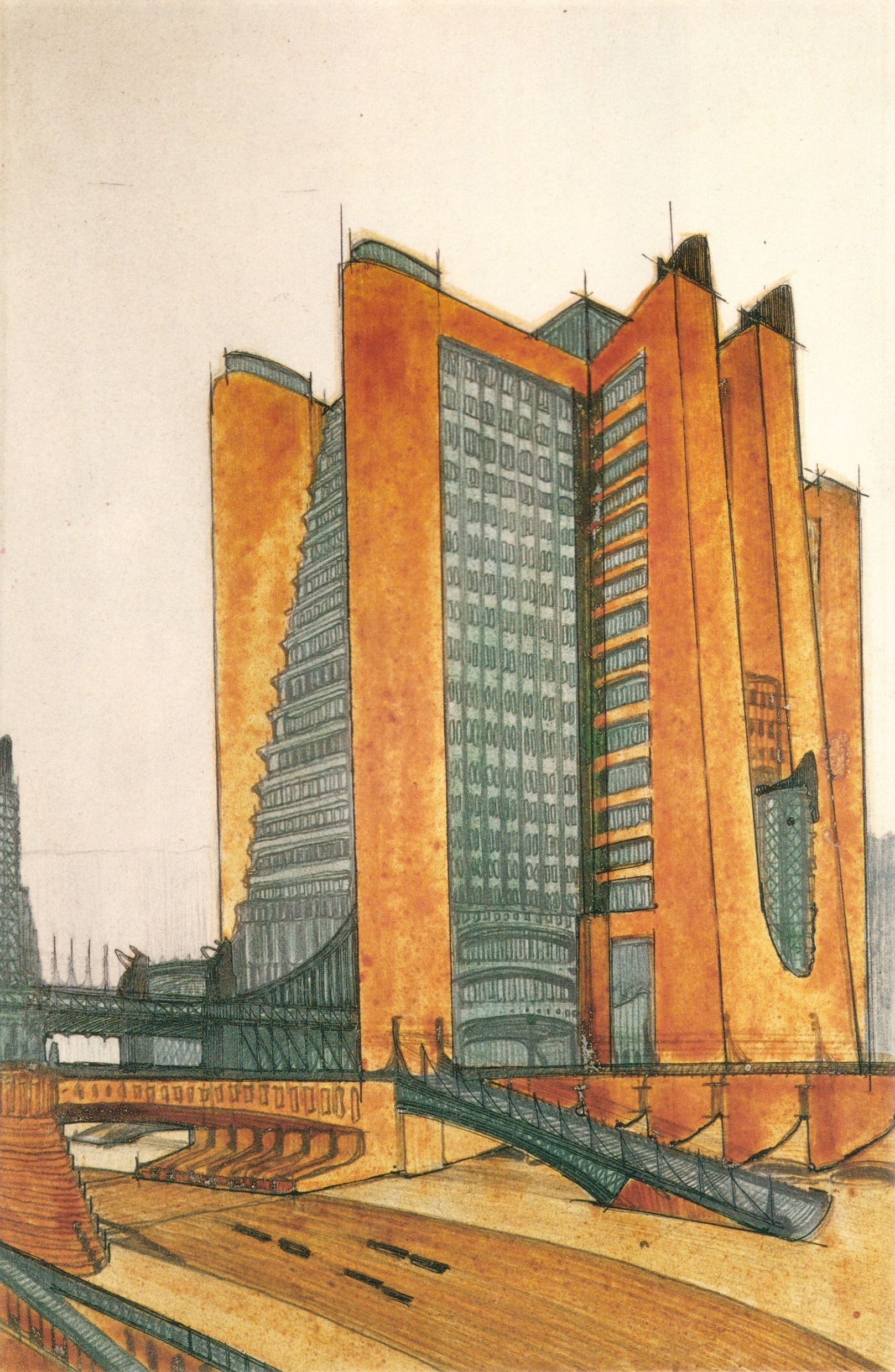

So breaking out of these fundamental assumptions of how roads should be is hard to do, even without the restraint of reality. Just ask the 20th century art movement The Futurists whose member Antonio Sant’Elia’s drawings inspired the design of the city in Metropolis. Their stated goal was to overturn centuries of stifled art and make Italy great again. They in turn were inspired by the machine age and the speed and energy it brought with it. In pursuit of this goal however they often ended up repeating the works of the past, making works that resembled those of the Ancient Greeks whose status they sought to displace.

For this reason we have to go deeper into what the current makeup of transport in our cities actually is. Importantly, why is it flawed? Roads become a problem when they take something away from us. Generally that thing is public space. We expand roads into anything that is not an otherwise defined space so they end up being the dominant form of shared space we experience in a city. Occasionally there are parks, public squares and purpose built spaces such as the Southbank arts complex by London’s Thames river, but the area of these places is vastly overwhelmed by roads.

We rarely have accessible spaces that are neither a designated focal point nor a medium of transport. Because roads are dedicated to motion, ordinary life can’t take place there. They become vacuums maintained to be as empty as possible for the fulfillment of speed on demand. This damages our communities in an immediate sense by bisecting them over and over with treacherous voids. It also does so in indirect ways by denying us a shared space to congregate in meaning people have to travel further to specialised venues to do the same and further increasing the dependence on roads.

One of a city’s marvels is the spontaneous connections that occur between people when they bump into each other. Ed Glaeser talks about this in detail in his book The Triumph of the City. If there is no shared space that functions as a residential extension, then we are limiting the opportunity for this to happen. Let’s not ignore the importance of this physical layer - it’s the physical manifestation of the intangible bonds that make up our society. The more meeting space we have, whether accidental or intentional, the better our politics functions. Squares can be filled with bodies, as the Ukrainians did the Maidan or people did Trafalgar Square during the poll tax riots in the UK and many protests since.

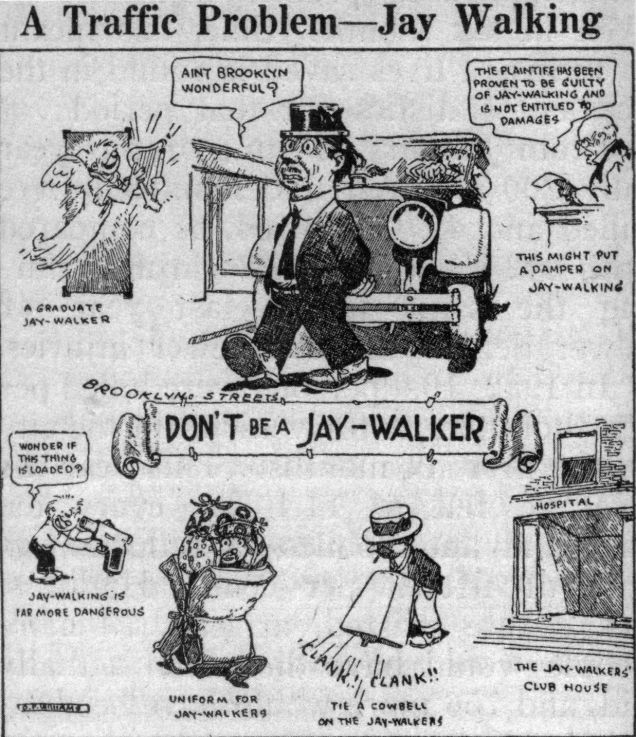

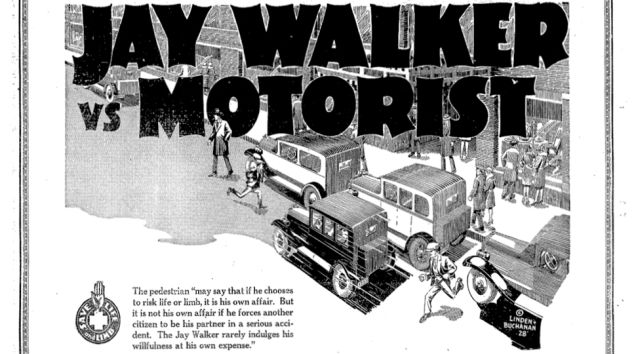

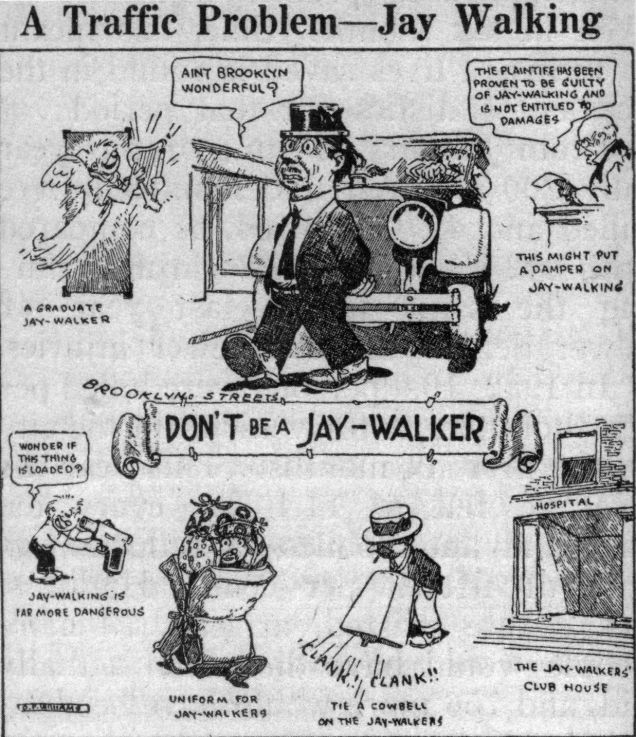

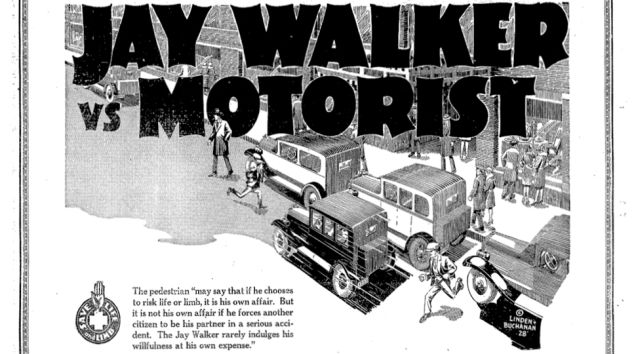

In the US there has been a greater attempt to manage the space we call the road with the invention by the car industry of an offence known as jaywalking. This wasn’t the legislative response to an inevitable problem but essentially a publicity campaign to increase car use in the US.

Prior to jaywalking becoming a popular term and crime pedestrians were assumed to have the right to the road. If there was an accident, popular opinion and the media would be on the side of the pedestrian and assume the fault of the driver.

The motor industry realised this was an impediment to people driving and set out to make the street a place for cars not people. They lobbied for various laws to prevent people from crossing other than at a designated point, but people were so against this that it couldn’t be effectively enforced.

What worked much better was public ridicule. The word jay means fool or rube, so the term jaywalking was appropriated in response to the use of the word joy driving by people angry at car users. A whole set of bizarre tactics were used including a man in a Santa suit shouting at ‘jaywalkers’ through a megaphone, a parade featuring a blundering fool being repeatedly shunted by a Model T Ford as he walked down the middle of the street and impromptu mock trials.

Legislation was created to similar effect, but it was the public humiliation and re-education of pedestrians, making society at large that people crossing the street where they felt like were idiots that worked best. In the UK the Green Cross Code (Stop look listen before you cross the road) is taught to children to help them not be run over. While there campaigns against drink, drug and tired driving there is no admonition of drivers for simply being foolish. The net effect of this is to teach children that they are at fault if they are hit by entering the dedicated area of fast movement.

Though the enforcement of jaywalking hasn’t survived everywhere, the derisive word has, and more importantly the idea that people not crossing at marked points are at fault for injuries sustained definitely has. The upshot of this strange tale is that the notion of what a road is more socially constructed than you might think. Its purpose and format are not dictated by technical design but by how we interpret technological change to affect our society.

The idea that roads should always be clear does not go unquestioned. Many cities around the world have experimented with car free days in varying degrees of totality, one of the largest being in Bogota, Colombia where the entire city bans cars for a day a year. Generally though, this space does not allow a great deal of freedom. There is the novelty of walking in a previously forbidden space but because they are temporary it does not allow any reconfiguration of structural concepts or allow social institutions to form within the vacant space. Report by Irish assembly on car free days.

Perhaps we’d better take a deeper look and find other ways of conceptualising the city. By taking a ground up approach we can develop a conceptual toolbox that allows us to formulate other ways of building the city. Our superficial view is that we have buildings with access that faces out onto a tarmacked road, often with raised edges we call pavements or sidewalks. It’s very difficult to come up with alternatives when thinking at this level since we’ve already determined on a mental framework of places and an intersecting network that surrounds it.

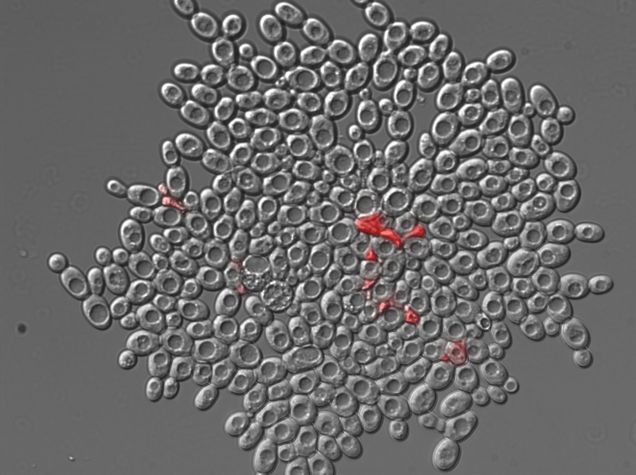

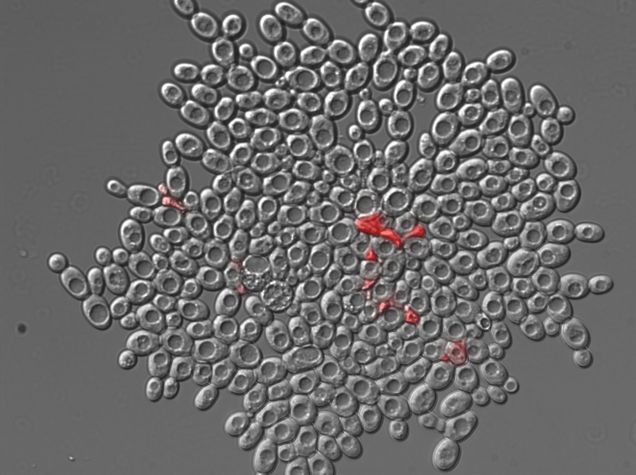

If we consider that we’ve made a choice to consider the fundamental unit of the city as the building or city block, which can be zoned or purposed, then we can change that unit to be whatever we feel is representative of the primary ingredient of a city. This could be people rather than buildings. Consider this image:

If that is the metaphor for a city that exists in your mind, it makes a huge difference what those cells are. If they are human beings, then we need to conceptualise an entirely different transport network. For the things that need to be carried from person to person - thoughts, ideas, love and anger. What kind of transport network could we imagine for that? Conversation or email? If we start to make planning decisions based on that notion then everything fundamentally changes in ways that are hard to imagine.

We’ll come to how what that might look like later on, but first I’d like to suggest another way of looking at a city: density. Yeah you know, what makes things sink. In terms of a city, density is usually defined as the number of humans occupying a defined measure of space. Not necessarily though, we could also measure the density of cars or rooms. If we choose any of those, again our design strategy changes and an entirely different city structure will result. I should note that when I say design here, I mean the unconscious collective emergent design that results from many people making microchoices based on a particular understanding of their surroundings. A driver’s choice to honk at someone crossing the road is a microchoice that is part of this design process.

What makes a city different from a village? Certainly a city is larger and has more inhabitants, but what really gives a city its character is density. Roads decrease density given that they are engineered to be as empty as possible and the objects that temporarily fill them tend to be much larger than the space a person might desire in a cafe say. Contarily, a bar or nightclub increases density by packing people close together and this is why people go there. So when you host a party, you are increasing the cityness of a city. In fact you are creating a mini city all of its own.

This is something that Corbusier and I agree upon: “The more dense the population of a city is the less are the distances that have to be covered. The moral, therefore, is that we must increase the density of the centres of our cities, where business affairs are carried on.”

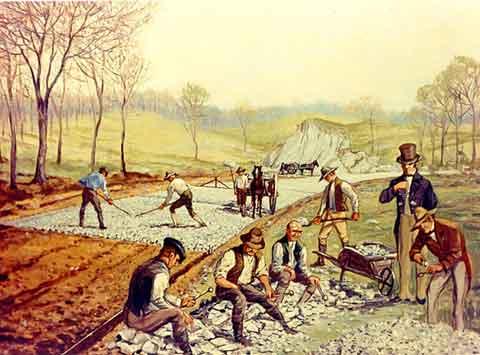

Looking at these conceptual understandings of transport’s place in a city is all well and good, but before we get into what they mean for roads, I think we need to go one level deeper and ask what is a road exactly? It’s a widening, flattening and hardening of a surface that leads from one place to another place. The first roads opened up new opportunities, making it possible to pass through previously perilous terrain.

Of course the historical sibling of the road is the corridor. They serve a similar purpose as a dedicated thoroughfare designed to allow passage from one place to another. Generally you don’t stop for too long, great memories of corridors are few and far between. Unless you’re at a party of course, in which case you might be hanging out in the corridor due to the human density of other rooms.

As obvious and fundamental as they seem now, corridors haven’t always existed. In 14th Britain, people slept together in the lord of the manor’s great hall. The lord and lady would have had a separate room they shared with intimate servants. Although in the Georgian period people with money started to disperse into private rooms they still didn’t design houses with corridors connecting them as this was deemed to be an inefficient use of precious space. Similarly, in pre revolution France, the nobility lived their lives in public, with people coming to see them in their private rooms and servants passed from room to room to go about their duties. Because of the easily understood distinction in status, there was no need to physically separate them. It wasn’t until the French revolution and all people were determined to be equal that there became a need to emphasise status based on the occupation of a physical space.

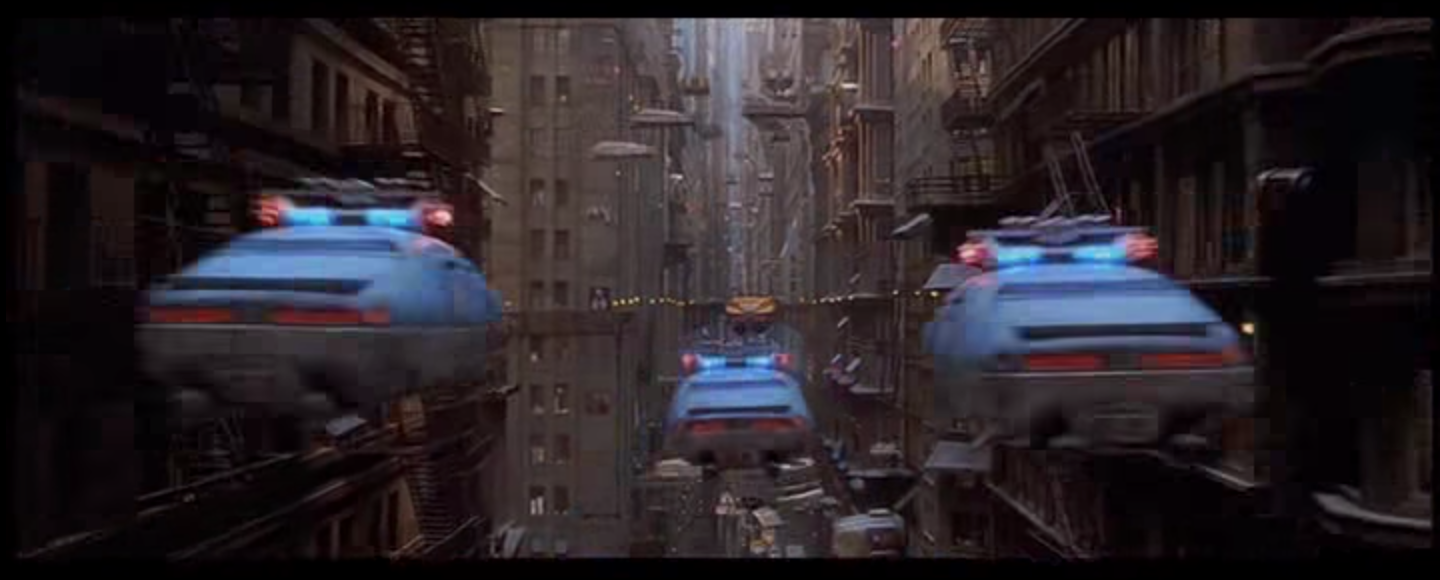

In parallel, demands were being made for improved roads. However the first calls came from riders of the newly invented bicycle rather than car owners. The Good Roads movement was founded in the USA in 1880 and petitioned for easier ways to get around by bike. At the time, roads were bumpy and slow and could be dusty or boggy depending on the weather. It was only by chance that the self powered vehicle was invented as the movement started to get results and the problem of how to accommodate different types of traffic became an issue with cars eventually winning out.

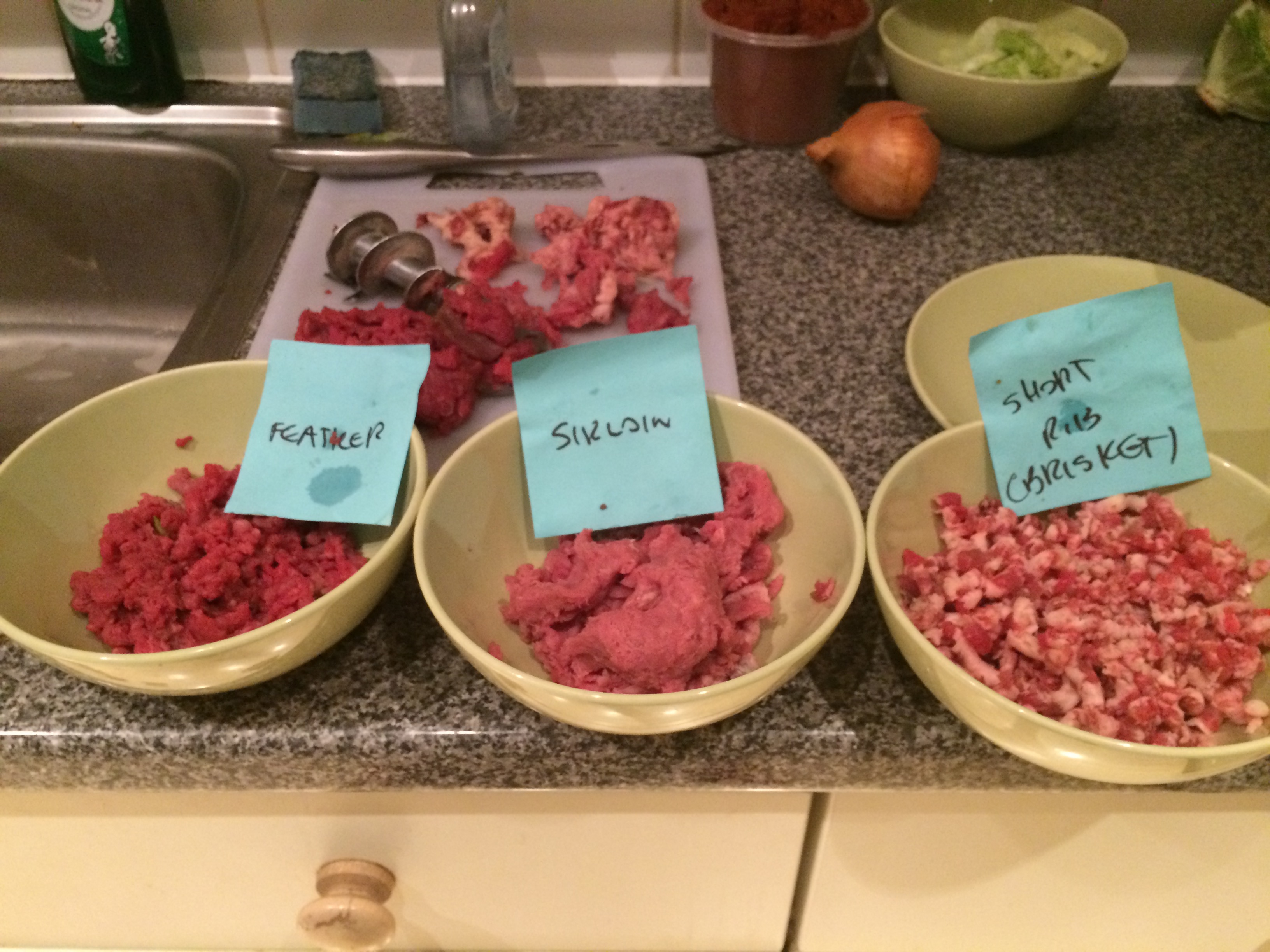

Road building techniques varied at first. Some were built with planks laid end to end providing a surface wide enough to drive on or parallel tracks wide enough for wheels. A man called John Macadam laid the foundations for today’s road building, laying down crushed soil and stone that sat tightly together to provide a generally smoother road surface. These came to be mixed with sand and eventually tar, providing the black surface we call a road now.

This development of roads is more political than one might realise at first. As well as the micropolitics arising from interactions while driving, cycling or walking there are the larger macro impacts of governmental politics.

Under the reign of Napoleon III, vast swathes of dense housing were cleared to build Haussmann’s vision of ‘the city of light’. The poor dingy slums which were a hive for infections were bulldozed and replaced by large grand boulevards and large public parks at a cost of hundreds of millions of Francs with builders working 24 hours a day.

However, as well as the ill health and cramped conditions of the slums, they were also difficult to manage given their complex network of streets and alleys, making fertile ground for revolts. In clearing away these tightly packed milieus they also got rid of the obstacles that prevented effective control. Similarly when Napoleon conquered Bologna in Italy boulevards were built to facilitate the marching of armies through the city.

This is an influence that has existed throughout history. Roman gridiron town patterns were designed to be thrown up in a matter of hours by an army on the move. During wartime, many highways were built in the US and Germany for the purpose of emergency landing of aircraft. We can see a modern day parallel to this in North Korea, where vast roads have been built that lie empty in preparation for an army to mobilise on.

Commerce has also had a deep influence on our roads, often making them wider and greater with vast parking lots outside shopping centres. And commerce has returned the favour most notably in the Googie architecture which primarily existed from the 40s to the 70s. It featured futuristic bold angles and was inspired by the raygun science fiction of the time. Independent travel was seen as part of this future, so cars and driving were heavily incorporated into the themes.

The styles were made to be seen from the car at high speed, so they stuck them into the air and decorated them with highly visible neon signs.

This takes us to present day Dubai, a city designed for excessive spending. Much as we’ve seen featured before in visions for planned cities, Dubai is littered with vast empty highways surrounded by nothingness. Given that it is an absolute monarchy, the composition of the city reflects its politics. Rather than places created by people in an ongoing process that serves themselves, it is a city designed in a top down fashion that serves external desires.

Interestingly though, the proliferation of Sheikh-ego boosting towers is actually an application of the principle of human density. The Burj Khalifa is a mixed use skyscraper currently the tallest in the world. The floors comprise homes, hotels, shops, restaurants and office space. It’s conceivable that one could live within the tower and never leave. While it is not also self sustaining in terms of energy and resources, it has the possibility to designate floors for hydroponic farming, waste and water recycling and power production which would make it so.

The Burj Khalifa bears a resemblance to Frank Lloyd Wright’s proposed tower The Illinois. Intended to be a mile high and built in Chicago, it was a giant tower with everything needed built inside. With these towers, elevators become the new roads. Futurist Sant’Elia was excited by the premise of vast buildings scaled by mechanical boxes: “Elevators must no longer hide away like solitary worms in the stairwells, but the stairs—now useless—must be abolished, and the elevators must swarm up the façades like serpents of glass and iron”. Movement by vehicle becomes redundant in this scenario because needs can be fulfilled within. This is the concept of simply not going anywhere. Returning to a state where going far afield is not so much an unthinkable dream, merely unnecessary.

However as we can see in Dubai, towers are frequently built for luxury purposes and have great infrastructural and resource needs that require heavy transport around them. So given that need, for now lets look at how we could integrate that transport into the general environment. If we don’t conceive of a transport network as a fundamental element of our city, then we are not bound to create roads in the first place. The car was invented over 100 years ago and while our technologies have changed, road design has merely improved in longevity and comfort rather than adapted to a changing society.

You will have heard of the Segway and possibly the Sinclair C5. Both are remembered as inventions hailed as revolutions but failed to take off, with the C5 entirely dead and the Segway enjoying a limited use. They are regarded as somewhat foolish and impractical because they are not suitable for road use due to the lack of protection they offer the rider. However there is nothing lacking about the designs themselves. Only that they do not fit into an existing infrastructure. Sant’Elia again: “As if we who are accumulators and generators of movement, with all our added mechanical limbs, with all the noise and speed of our life, could live in streets built for the needs of men four, five or six centuries ago.” Indeed we are now furnished with many more opportunities for powered movement than he could have imagined. Yet we still constrain ourselves to an inefficient single purpose format.

“The modern street in the true sense of the word is a new type of organism, a sort of stretched-out workshop, a home for many complicated and delicate organs” ~ Le Corbusier

Here Corbusier is talking about a workshop in terms of infrastructure, arguing that what is currently buried beneath the streets should be easily serviceable. We can expand that definition to mean the workshop of our lives - the place where we tinker, experiment and explore alongside each other. We should free our minds from the definition of streets as empty spaces and consider them extensions of residential, social and business spaces. Because the space doesn’t need to kept clear, the sharp divide between what is somebody’s and what is simply some space is far less relevant.

In this shared space that is not designated for traffic, which is what the streets partially were before the advent of the motor car and the invention of jaywalking, we can adopt different and more suitable forms of transit. In a world of narrow gaps, uneven surfaces and low speeds, a person sized electrically powered vehicle is ideal to get around.

Previously the aim was to create as much space on the road to fulfill all transport needs without any congestion. It’s since been established that the more capacity created the more demand rises. This is known as induced demand and Los Angeles’ traffic jams are testament to it. Thought in urban planning has turned to creating pleasant livable streets and often this involves narrowing them and banning certain modes of transport. In the age of the autonomous vehicle and agile robots it might be easier to let computers navigate these crowded and complex streets. Autonomous vehicles are capable of recognising other road users and navigating around them more safely than humans, so there is less need to separate pedestrians and vehicles. See Bjarke Ingels for more.

Does this go far enough though? Given that roads are the dividers between places, if we remove them we are also questioning buildings as the basic unit or cell that forms the body. Bodily metaphors are often used for cities. They have centres as hearts, parks as lungs and arteries that provide flow. This is no longer an appropriate metaphor. The imagery we make use of to understand our cities affects our roles in them. I suggest we see roads as cords that bind and trap the city, preventing it from expanding organically.

If roads do not need to be kept clear, then we can have semi-permanent or permanent structures that fill that void. These don’t have to replicate existing buildings, since they are designed to interface with a road and provide vehicular access. Long distance travel can be provided by underground or elevated trains that transition to ground level train track once reaching the countryside to avoid impeding the pedestrian. Local travellers are compelled to explore their environment and interact with it and other people during their journey. Some travelling may take slightly longer, but the magic of the city is created by mysteries, so some of the efficiency of the transport function will be sacrificed in aid of fun and exploration. An example of this is Leopold Lambert’s Nausicaä Gardens, shown below. Imagine a whole city structured like this where movement is simply an interaction with the whole, rather than a separation from it.

There are also number of ideas around differently structured roads. Harvey Wiley Corbett in 1913 proposed a multilayer structure that would separate pedestrians from traffic entirely.

Chicago has multilevel streets that separate traffic into various layers depending on destination. The top level serves local traffic and lower levels serve through traffic.

We can take density another level further. How about no open space at all? There are some places in the world that due to historical conditions are so dense as to have no roads at all. The most famous of these was the Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong, demolished in 1994. Because of its semi-lawless state, it was a place where refugees could settle and filled it to a population density of 3.2 million per square mile. While much like pre-Haussmann Paris the argument for demolishing it was that it was a dingy run down place - there were few sources of water and a single tap was shared by hundreds of residents - there is nothing that makes that inevitable. While there was a high degree of criminality within the city, for most people life carried on as normal and it featured an entire ecosystem with shops, butchers, schools and brothels inside.

The Kowloon Walled City does have some very narrow corridors connecting parts of it together. If we combine this level of density with the medieval approach to building houses without corridors, we have a city that does not even know the notion of roads. This could be a city where rooms are temporary function based rather than unit based. Talking about the walled city Leung Ping Kwan writes in The City of Darkness that “what were children’s games centres by day became strip show venues by night”. In no other period but our own could this make sense; we’ve never had the density of people to create it. If you take an open area of land and build a house on it then you still have the remainder of space which the house is an interruption to. We are not building single houses anymore, we’re building cities. That requires a different set of rules to the accumulation of single houses that happen to be near each other. Most of us would prefer to reside somewhere more salubrious and with the option for more privacy than Kowloon Walled City, but we should take into account what it means conceptually to abandon roads in a city and how we can take parts of that into our own design.

There is another option which I would like to investigate in more detail elsewhere. That is the movement of the buildings themselves, again negating the need for any division between places and road-voids.